How to Lose a Legacy

Essay from The Opinonater, The New York Times

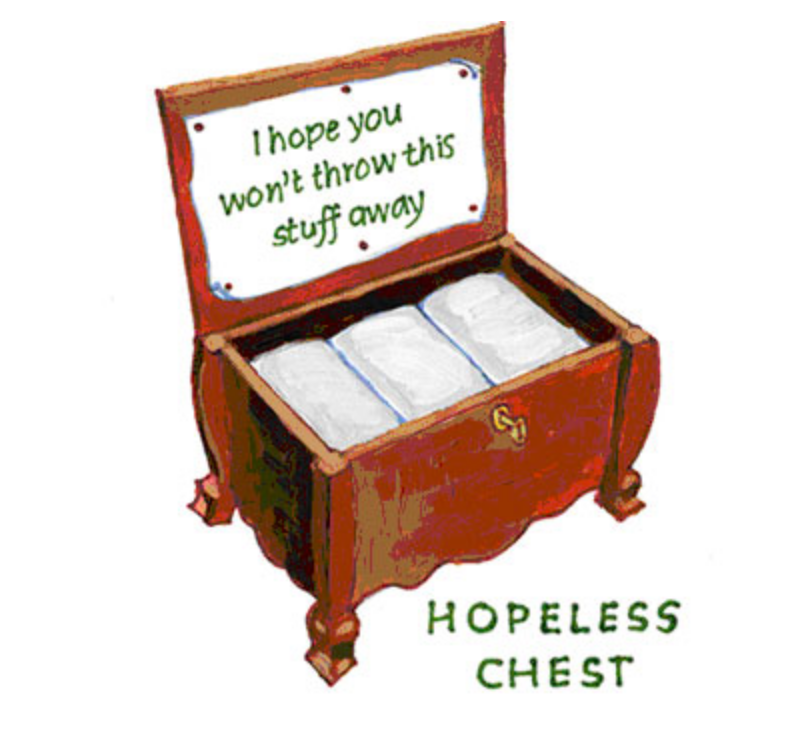

An “heirloom” is an object steeped in family history, handed down from generation to generation: your mother’s wedding dress, your grandma’s espresso cups, your great uncle’s underwear. You can’t buy an heirloom at Pottery Barn or Ikea. It comes via gift, bequest or a heated sibling brawl. But who’s to say you actually want this stale old stuff?

The desire to pass objects on to one’s offspring is part of our longing for immortality. Even folks in the “die broke” crowd, determined to enjoy their remaining assets rather than leave them to the ungrateful grandkids, may secretly hope the family will love and honor their dearest possessions. In a culture of scarcity, useful things are rarely discarded, but in a land of superabundance and incessant newness, inheriting a household packed to the windowsills with books, furniture and memories of drunken holiday infighting can be more burden than blessing.

Heirlooms aren’t just hand-me-down artifacts anymore. Fruits and vegetables with ancestral pedigrees are a surging trend in farmers’ markets and garden centers. When confronted with my first heirloom tomato a decade ago, I wondered, why does it have to be so ugly? A splotchy mass of unruly, misshapen lobes bursting out in all directions, this high-priced agro-oddity posed a sophisticated alternative to perfectly shaped hybrids. But I find it hard to beat the robust flavor of a Jersey tomato in July, its physique as toned and glossy as a beach body from “Jersey Shore.”

Appearances aside, heirloom fruits and vegetables represent the leading edge in sustainable farming, owing to their unique genetic characteristics, which agronomists would like to protect. The Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, preserves genetic material for more than 25,000 “endangered” vegetables. And now avid cooks and slow food aficionados can also buy or raise their own heirloom livestock, from Blue Foot chickens to Red Wattle pigs. Growing these rare breeds and slaughtering them for food keeps their imperiled DNA alive.

Objects risk extinction, too. Antique stores are filled with failed heirlooms — that faded quilt or knotty pine commode that was abandoned by its owners, or worse, its owners’ children. Nicole Holofcener’s film “Please Give” revolves around an antique dealer (played by Catherine Keener) who acquires the possessions of recently deceased apartment dwellers and sells them for a profit in her hip urban furniture shop. While she frets about the morality of the postmortem markup, her pragmatic husband (Oliver Platt) sees what they’re doing as a service for middle-aged offspring who want to cut loose from old baggage (and some very ugly vases). That musty smell in your favorite antique store? It’s death warmed over, served with a splash of vintage vinegar.

Although my own house contains many midcentury objects rescued from oblivion by shops like the one in “Please Give,” my husband Abbott and I possess only a handful of official heirlooms from our own family, including a set of Wedgwood cornflower blue china inherited from my mother’s mother and a mounted deer head passed down from Abbott’s grandfather. The glassy-eyed beast followed us loyally through our youth in a series of East Village apartments to our current renovated lodge in a woodsy Baltimore neighborhood. Although it finally seems at peace here, surrounded by trees, installing it was an emotional battle. “It makes me sad,” our 11-year-old daughter said. “And it’s embarrassing. My friends will think it’s weird to have a dead animal in our living room.” My husband tried defending the artifact on ethical grounds (“We didn’t kill it”) and then on decorating grounds (“It looks fabulous with the Ted Muehling vases”) before finding his last defense: “It’s the only thing I have from my granddad.” This argument worked; the doe’s second execution was stayed by its status as an heirloom.

Dust unto dust, the saying goes — and books, hat boxes and ceramic figurines unto dust. Especially books. Unlike speech, text survives when the writer is long gone. The voice fades but a well-bound book could last forever — as long as someone bothers to keep it on a shelf somewhere, clean, dry and free from the onslaught of hungry cockroaches. (They feast on the glue used in bindings.) Books dominate our house, thousands of them, mostly about art and design. Despite ruthless periodic purges, new volumes creep in. Our kids are mystified: “Why do you have so many books?” A vast personal library — once the sign of well-schooled intellect — may be more bewildering to the rising generation than a collection of mounted game heads.

We love our library, which entombs a lifetime of fleeting interests and enduring obsessions, but we’re also oppressed by its physical and emotional weight. Like many others, we worry about what will happen to all these volumes when we’re gone. Do books have souls? Is there an out-of-print afterlife? Do midlist titles die and go to hell on a flaming Kindle? Every year, Jennifer Tobias, a librarian, receives many offers of personal libraries; rarely are these acquired in full. Even a single text must meet exacting standards before making it into a library’s collection. She advises people seeking to unload their books to be realistic about the usefulness of any volume (does your local high school truly need a book about postmodern teapots or Photoshop 1.0?) and to discard anything afflicted with mold or mildew, which can spread to other books.

If you lack the courage to sell or destroy your superfluous belongings, you can put them in storage. Rented cubicles are a costly form of denial: you don’t really want these things, so you send them away — often for good. Self-storage, says Richard Burt, a professor of English at the University of Florida, is about storing the self. When we place our personal effects in an air-conditioned locker, we put away part of our physical and emotional being, keeping it on life support for as long as we can foot the bill.

Premature heirloom loss can be devastating. The novelist Jessica Anya Blau told me that when she was separating from her first husband, she relocated to another city to attend grad school while he placed their combined possessions in storage. Blau left behind things she loved but could survive without for a while, including albums of baby pictures and some silk dresses and pink china from her grandmother. Alas, her ex neglected to pay the rent on the storage unit, and all its contents were auctioned off, gone from her life forever. Her first reaction was shock and desolation. These were cherished things that couldn’t be replaced. But dismay quickly gave way to feelings of lightness and freedom. She had come to enjoy living in an open space unburdened by things. It felt good to be emptied out.

Physical possessions are, indeed, a burden. They gather dust and take up space. They also lose and acquire meaning over time. I probably wouldn’t have kept those blue dishes if I had bought them in a junk shop 20 years ago. But they were my grandmother’s, so I keep them safe, and take them out a few times a year for family celebrations. As I wash each piece by hand, I wonder, with a pang of melancholy, if my daughter will someday do the same. Maybe, and maybe not.